Overview

- The first North American detection of golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) was in October 2024. Although this mussel is similar in appearance and impacts to quagga and zebra mussels, it can establish in waters with wider temperature and salinity ranges.

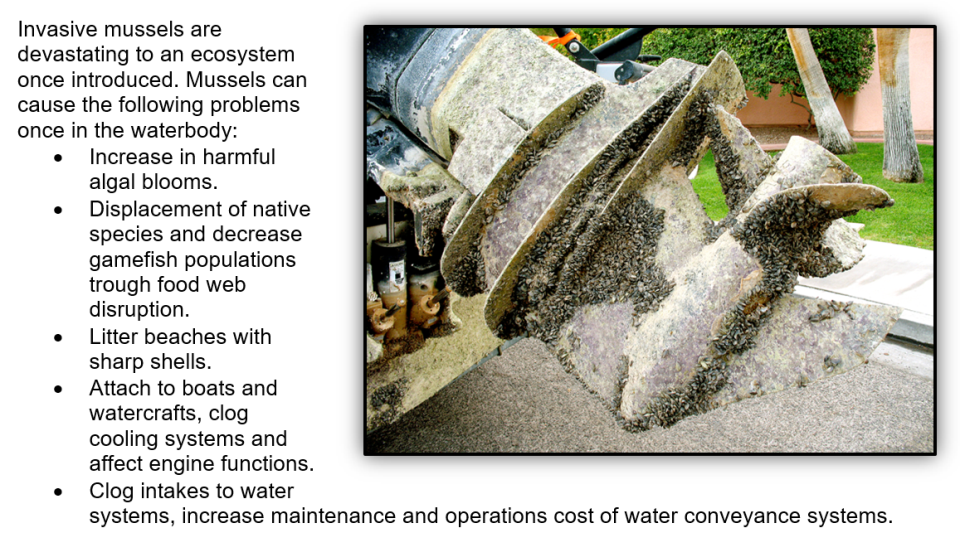

- Environmental impacts include loss of native and game fish through competition for the same food sources and as a contributor to harmful, fish killing algal blooms.

- Recreational impacts of this mussel include waterbody closures, mandatory inspections, reduced numbers of fish and shellfish for consumption, increased launch and/or entry fees.

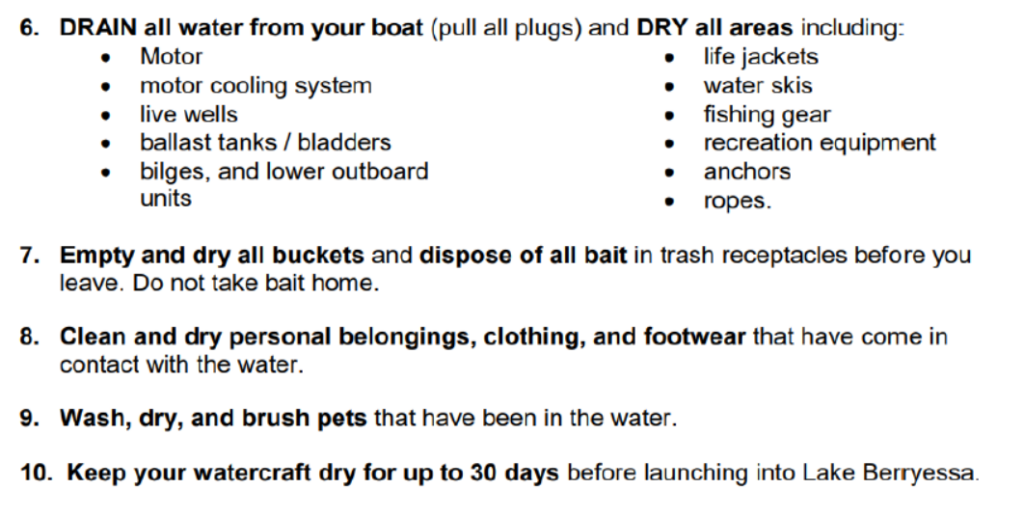

Mussel’s can attach to hydroelectric equipment

Examples of Scale:

Quagga, Zebra & Golden Mussel Facts

Physical Description: Golden Mussels are sessile (non-moving) bivalves (two-shelled mollusks) whose color varies from a light golden to darker yellowish-brown and brown hues. Adult shells are typically 2-3 cm in diameter, with some reaching sizes of >4 cm. Golden Mussels typically grow in dense, reeflike colonies containing as many as 200,000 organisms per square meter.

Habitat: Originating from China and southeast Asia, Golden Mussels now inhabit shallow (< 10 m), freshwater aquatic environments worldwide. They tolerate many environmental stressors including wide ranges of temperature, pollution, and low oxygen. Preferring fresh water, Golden Mussels can nevertheless tolerate salinity of up to 10 ppt for as much as 30 days (Sylvester et al., 2013).

Life History: Mussel larvae develop into mobile veligers that propagate through a water body before reaching the settling (plantigrade) phase roughly 11-20 days after spawning. They then colonize hard surfaces and grow into adult mussels. Once attached, they remain sessile indefinitely.

Ecosystem Impacts: Golden Mussels are highly-effective ecosystem engineers, with the potential to catalyze broad-scale environmental change equivalent to invasions by Zebra or Quagga Mussels. They can dramatically reduce the abundance of both zooplankton and phytoplankton, leading to widespread food web impacts. Mussel invasions elsewhere have been associated with an increased frequency of potentially-toxic blooms of Microcystis. Their propensity to rapidly colonize any available hard surface jeopardizes built infrastructure in any infested water bodies.

Monitoring Notes: Golden Mussel colonies typically attach to solid substrates, preferring piers, moorings, rocks, downed trees, or other submerged objects. The do not grow in soft, unconsolidated sediments and are therefore unlikely to be detected using typical methods for monitoring the benthos (e.g., grabs and cores).

Quagga & Zebra Mussels

Quagga Mussels (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis) are a small freshwater mollusk. They are an invasive species native to Russia and Ukraine and are thought to have been transported to the Great Lakes region in the ballast water of transoceanic ships. They have some diagnostic features to identify them from zebra mussels. The quagga’s shell has a rounded angle, a convex ventral, and their color varies from black, white, cream, but they are generally paler (U.S.G.S.). The quagga causes problems because they are “water filterers” and are able to remove large amounts of phytoplankton and suspended particulates from lakes and streams (Sea Grant Michigan). This can have a potential to alter the balance of the aquatic food web. The mussels’ tissues also trap contaminants, which can be exposed to wildlife if they are eaten. Like zebra mussels, the quagga also clogs water structures that can reduce pumping capabilities for water treatment (Sea Grant Michigan).

Zebra mussels, a native species of Eastern Europe, were first introduced in the United States through ballast water released into the Great Lakes in the late-1980s. Quagga mussels soon followed.

Great efforts have been made to prevent the spread of these fresh water mollusks west of the 100th Meridian. In January 2007, Quagga mussels were discovered in Lake Mead and later in other reservoirs of the Lower Colorado River. Quagga mussels were discovered by Metropolitan Water District divers on Wednesday, Jan. 17, 2007 at Lake Havasu, and again on Friday, Jan 19, 2007 about 14 miles to the north. In January 2008, Zebra mussels were discovered in San Justo Reservoir in San Benito County, California. The spread of these mussels to additional California waters will seriously impact the state’s aquatic environment and water delivery systems, endangering recreational boating and fishing.

What Makes These Mussels So Invasive?

There are four primary characteristics that make these mussels incredibly invasive:

- FREE SWIMMING LARVAE – Larval mussels swim in the water column for the first month of their life. Because they are free swimming and extremely small, they can be drawn into engines, ballast tanks, live wells and bilges, and be easily transported from one body of water to the next.

- BYSSAL THREADS – Zebra, quagga and golden mussels have byssal threads that allow them to attach to any stable substrate in the water including rocks, plants, fiberglass, plastic, cement, steel, and even onto other mussels creating a thick layer as seen in some of these photos.

- RAPID REPRODUCTION RATE – They have a very rapid reproduction rate, spawning year-round (if conditions permit), where 1 single female can produce up to one million eggs in a year.

- FILTER FEEDERS – Feeding off of plankton (the foundation of the aquatic food chain). It has been observed that a mussel can filter up to a liter in a day. Anything they have filtered through that they do not eat is rejected as a mucous known as pseudofeces. This pseudofeces is known to decrease DO and increase pH.

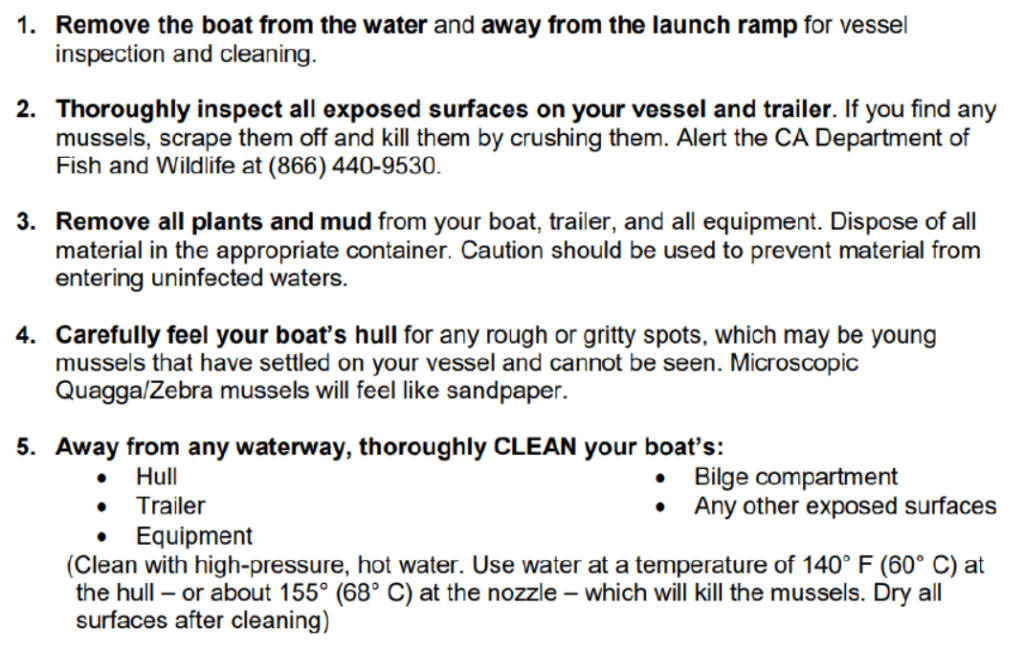

What to do if you think you have been to an infested waterbody?